Condition of Oyster Harbour

The Regional Estuaries Initiative supported the ongoing water quality, seagrass and macroalgae monitoring of Oyster Harbour since 2016 with monitoring continuing through Healthy Estuaries WA.

Below is the latest data about the condition of Oyster Harbour.

For more detail on the condition of Oyster Harbour, read Oyster Harbour: condition of the estuary 2016-19 or Water quality snapshot: Miaritch (Oyster Harbour) 2021–22.

Water quality is also measured upstream and downstream of the Centennial Park Wetland to monitor it's effectiveness at removing nutrients. Find out more about this monitoring here.

Seagrass in Oyster Harbour

Seagrass meadows are an important part of estuarine ecosystems, providing habitat and food for birds, fish and crustaceans. They contribute to good water and sediment quality by consuming nutrients and oxygenating the water and are estimated to provide $12 million per year in ecosystem services to WA estuaries. Seagrass meadows also store carbon and release oxygen – making them a strong ally in the fight against climate change.

Seagrass condition and distribution throughout an estuary can provide important information about the overall health of the estuary and the quality of water entering it from streams, creeks, rivers and drains.

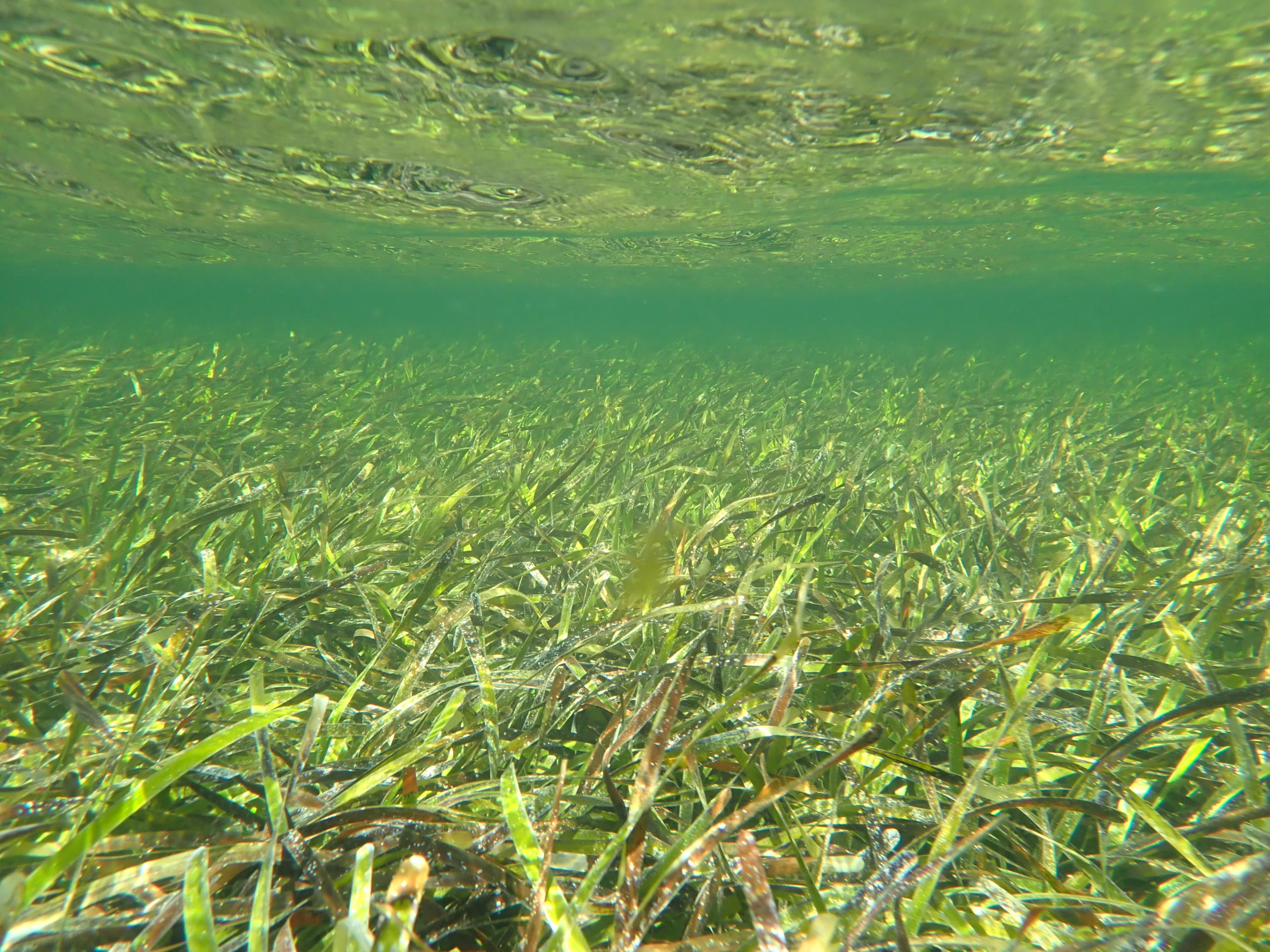

The seagrass habitat in Oyster Harbour includes two species: Posidonia australis and Posidonia sinuosa. These species look similar, but Posidonia australis has wider leaves than Posidonia sinuosa.

Posidonia australis

Seagrass distribution in Oyster Harbour

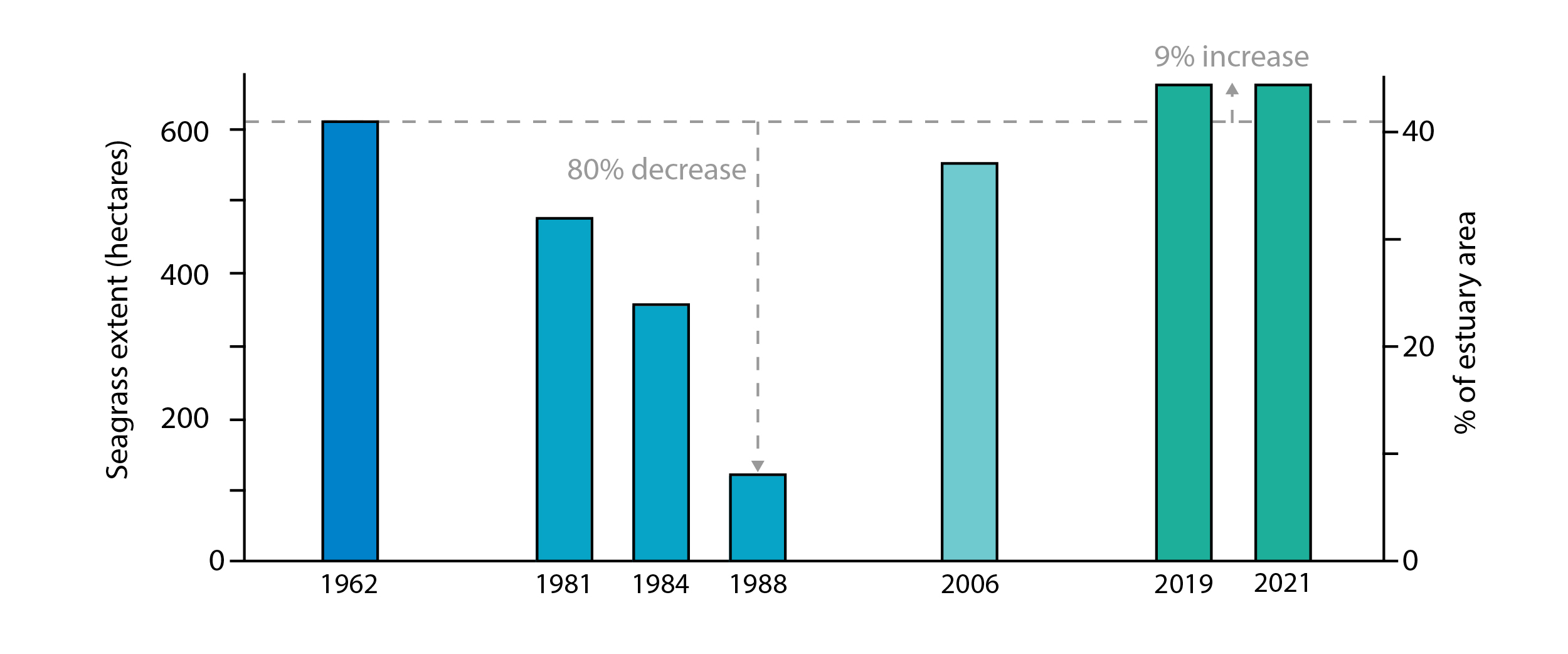

- In 1962, seagrass was distributed across 610 hectares.

- About 80 per cent of seagrass was lost in 1988 because of light reduction and excess nutrients, which promoted epiphyte growth.

- By 2006, seagrass recovered to span across 560 hectares, or 40 per cent of the estuary area.

- In 2019, seagrass had further recovered, extending across 663 hectares, or 50 per cent of the estuary area (nine per cent more than what was recorded in 1962).

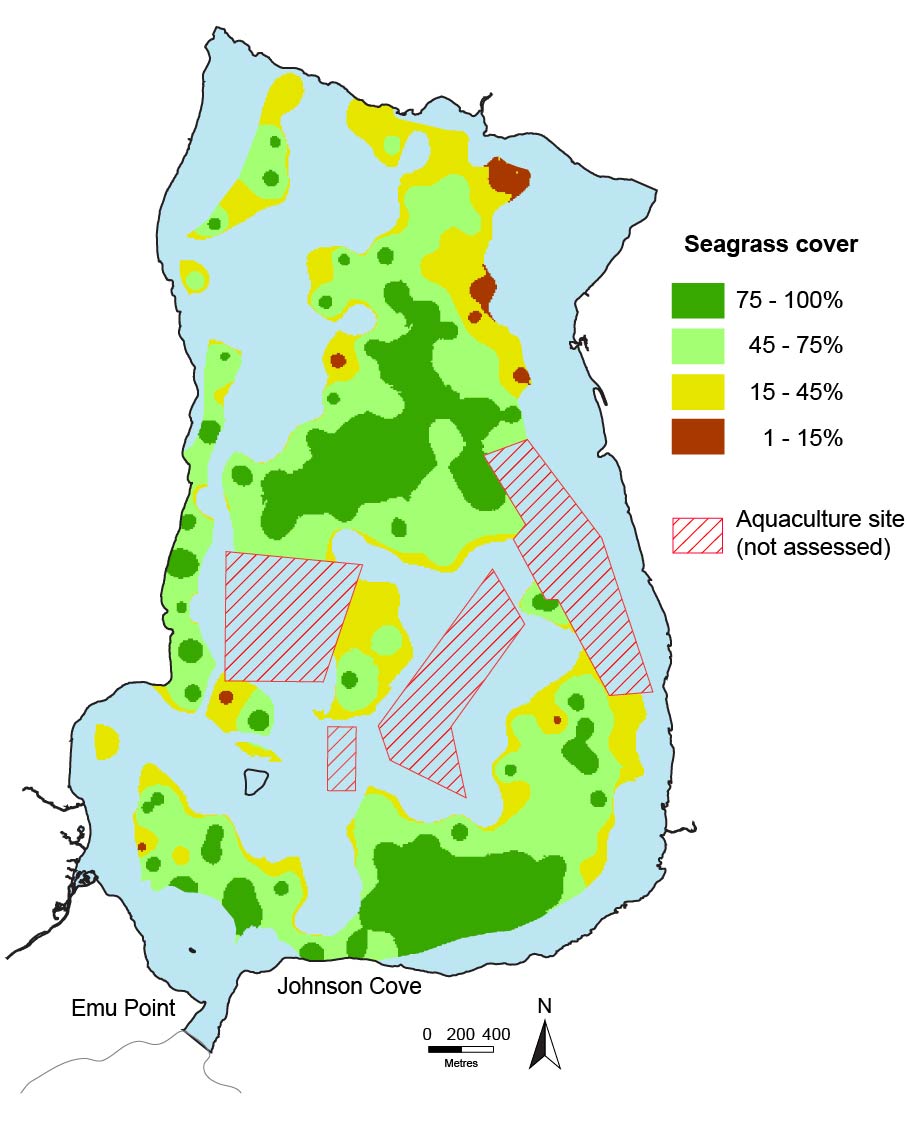

Seagrass distribution in Oyster Harbour

The extent of seagrass meadows in 2021 is consistent with 2019, improving slightly from about 663 hectares in 2019 to 665 in 2021. The highest-density meadows were found along the southern bank near Johnson Cove and in the central basin. Posidonia australis is found throughout the estuary, while Posidonia sinuosa is mostly found in the lower half of the harbour. In 2021, seagrass canopy height was typically around 50 cm, but ranged from 10 to 100 cm.

Macroalgae in Oyster Harbour

Macroalgae (or seaweeds) are a vital and natural part of many estuarine and marine ecosystems. They provide important habitat and food for many creatures, and perform essential ecological functions like oxygenating water and absorbing nutrients. However, an overabundance of macroalgae can become a problem, and often indicates too many nutrients in the water. Macroalgae can therefore be indicators of water quality. Assessing macroalgae in estuaries forms part of our integrated understanding of ecosystem health.

There are many different macroalgae species (which should not be confused with seagrasses). These are generally grouped based on their appearance or pigments in their tissue. The groups are red algae (Rhodophyta), brown algae (Ochrophyta) and green algae (Chlorophyta).

Excessive macroalgae growth was previously an issue in Oyster Harbour. A historical survey from the late 1980s showed excessive growth of Cladophora species – a green macroalgae. This species dominated the estuary, making up more than 90% of the algae biomass. Other algae observed during this period included green algae such as Chaetomorpha and Ulva species, as well as comparatively small amounts of unidentified red and brown algae. This overabundance resulted in macroalgae harvesting in the 90s, which saw more than 30,000 tonnes of algae removed over a period of seven years.

The macroalgae was harvested to reduce some of its negative effects, such as oxygen depletion and foul odours, as well as increase the likelihood of seagrass recovery. Another option was to manage the source of the problem, rather than dealing with the consequences, by reducing nutrient inputs to the harbour. This became the preferred plan, and eventually replaced harvesting. In the decades since, there has been a remarkable recovery of seagrasses in the harbour and a reduction in nuisance algae growth.

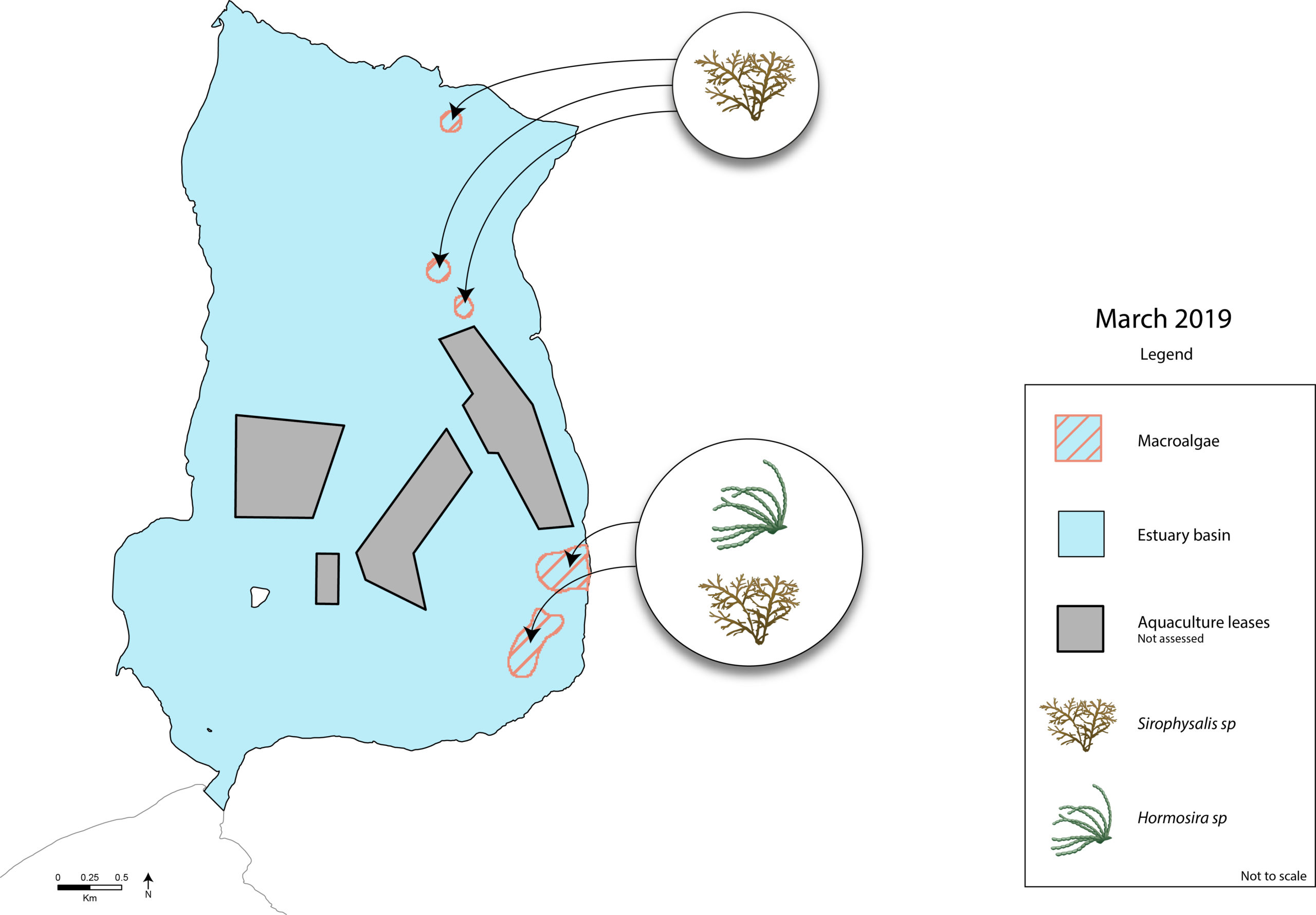

As part of the Department of Water and Environmental Regulation’s seagrass monitoring, a snapshot study occurs during the summer months in the Oyster Harbour in survey years. In the summer of 2019, two types of brown algae were recorded: Neptune’s necklace (Hormosira banksii) and Sirophysalis species. At the time of the survey, macroalgae were observed on 5% of occasions with very low cover (approximately 5%). Macroalgae were confined mostly to the eastern parts of the basin, as well as near areas used for aquaculture and close to the river mouths. Aquaculture leases were not included in the survey.

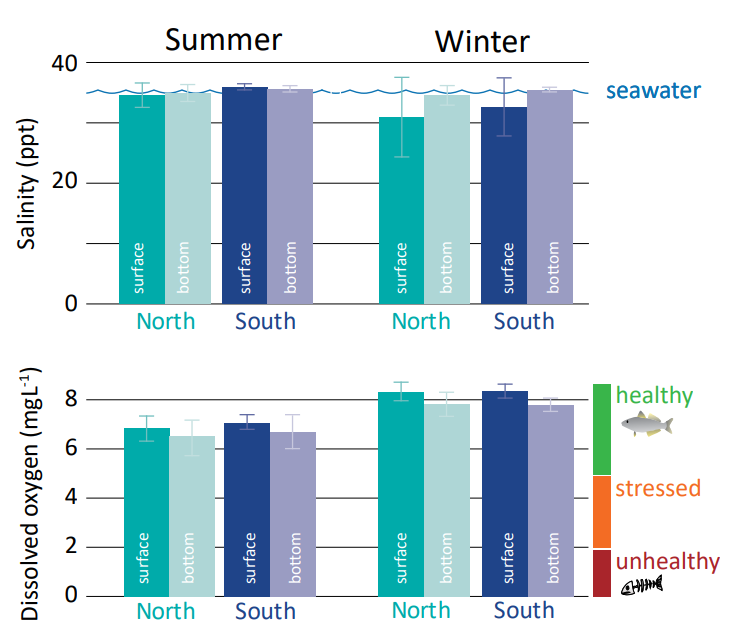

Salinity and oxygen concentrations (2016-19)

In summer, the salinity levels of both surface and bottom waters in the north and south of Oyster Harbour are close to being at marine levels. The average dissolved oxygen values were in the healthy range. Bottom dissolved oxygen was slightly lower, particularly in the north of the harbour. This is due to the breakdown of organic matter, which consumes oxygen – a typical process in most estuarine ecosystems.

Winter salinities were slightly lower in the surface waters and varied more, due to the influence of fresher river inflows, yet remained in the ‘saline’ zone. This indicates river inflows have a relatively small impact on salinity. Average oxygen concentrations were well within the healthy range throughout the period.