Peel-Harvey Estuary

The Peel-Harvey Estuary is the largest and most complex estuarine system in the South West, with an area of 134 square kilometres. It forms a key part of the Peel-Yalgorup wetland system – a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention. The wetland system is important for waterbirds and waders, and regularly supports more than 20 000 birds. It also supports the regional fishing economy and is used extensively for recreational purposes, particularly boating, fishing and crabbing.

The Peel-Harvey Estuary has a long history of water quality problems. Since European settlement, drainage throughout the catchment has been heavily modified and has increased the amount of nutrients entering the rivers and estuary. The first of many mass fish mortalities in the estuary occurred in 1907 and was attributed to the increased input of silt due to drainage modifications.

The estuary suffered ecological collapse in the 1970s-80s due to excessive nutrient loads being transported from the catchment via the rivers and drains. Extensive and persistent blooms of toxic microalgae in the Harvey Estuary and macroalgal blooms in the Peel Inlet destroyed the ecological health of the estuary and seriously constrained recreational use and economic activities such as fishing and tourism.

Part of the state government’s solution to these problems was to increase marine exchange in the estuary by constructing the Dawesville Channel in 1994. This improved the water quality in the main estuary basins through increased ocean water exchange. Recent signs of poor water quality in some parts of the estuary are directing us to catchment actions that will ensure nutrient pollution is minimised.

Aboriginal significance

The Peel-Harvey estuary sits inside the boodjar (country) of the Bindjareb (Pinjarup) Noongar people. The Binjareb people refer to the Peel-Harvey estuary as Djilba.

This is the ancient name used for thousands of years.

Djilba is also a name for one of the Noongar people’s six seasons and runs between August and September, straddling the western European seasons of spring and winter. Djilba is also a name for the fish, bream.

Djilba‘s values are associated with renewal and re-birth, including bream that start to spawn in the estuary around spring time each year.

According to the local Noongar people, the Peel-Harvey estuary, and all the rivers and lakes that are connected to it, were formed in the Dreamtime, when there was a drought on the land and the freshwater sources were drying up.

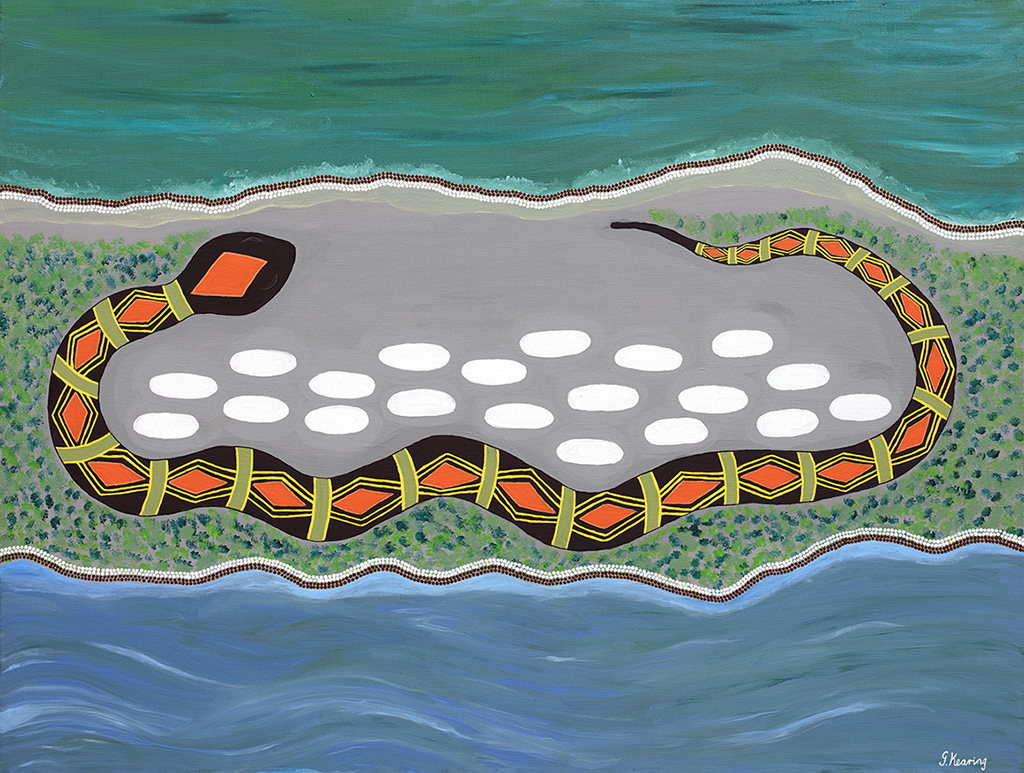

The Noongar creator being, the Woggaal, is associated with the creation of freshwater places in the Dreamtime. The Peel Inlet was created by the female aspect of the Woggaal, known as Maadjit, when she went inland from the sea to give birth to her children.

Other parts of the Peel-Harvey’s surrounding rivers, streams, lakes, waterholes, wetlands and springs were formed by Maadjit’s children or koolaangka as they left the estuary and travelled throughout the country leaving their own marks and trails.

Finally, the remainder of the waterways were formed by Maadjit as she searched for what became of her children.

Djilba‘s values are associated with renewal and re-birth, or what we would refer to as spring values. Djilba’s values are also specifically referred to by some Noongar groups as incorporating the ‘second rains’ that ‘fill lakes and waterholes.’

Djilba is also one of the Noongar names for bream, which live and are abundant in the south west waterways, including the Peel-Harvey, and which start to spawn in the estuary around spring time each year.

In cultural knowledge, the relationship between the environmental values of Djilba and the Dreamtime story of the creation of the Peel-Harvey Estuary system are clear. The birth of the spirit children of Maadjit comes at a time of drought, and through the birth and subsequent life of the children, new freshwater rivers and waterholes are created, and the fertility of the land is re-set.

The values of bream are also elegantly embodied by Djilba. Bream were, and remain, a major food source of Noongar people. They start to spawn during the sixth Noongar season, and unlike many species that give birth in estuaries only to move to ocean, the bream spend their entire lives in the estuary, where the ebb and flow of saltier and fresher water plays a key role in the timing of its movement and life cycles.

In respect to the Maadjit, the Murray River is called Bilya (River) Maadjit (Female Creator) therefore the bridge where the Kwinana Freeway ends and where Forrest Highway begins is named Bilya Maadjit.

*Cultural informants George Walley, Cultural Knowledge Holder, and Joseph Walley, Senior Elder and Cultural Knowledge Holder (RIP).

How the Waters came to be

One day the Aboriginal people of the Mandurah area found there was no waterways, they went to the beach and danced and sung for the great Waugal to come. Then she came and started to make the Peel Inlet and the estuary, she found that she was carrying eggs and she rested in between the estuary and the sea until she laid them. This painting shows that she layed with her eggs to keep them safe. Then the eggs hatched and she sent her babies to do the rest of the work because she was tired.

She sent one up the Serpentine, one up the Murray and one up the Harvey and that’s how they came to be.